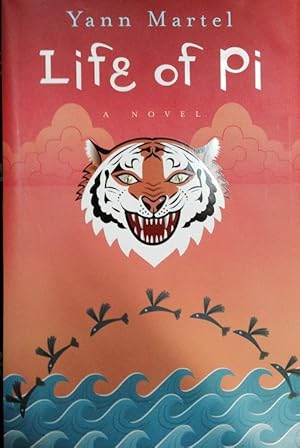

This paper will question the seeming inexhaustibility of the survival story as Life of Pi belongs to a long tradition of survival narratives that range from Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719), William Golding’s Lord of the Flies (1954) and Moacyr Scliar’s Max and the Cats (1981) to more popular Hollywood films such as Robert Zemeckis’s Cast Away (2000) or J. The regular revisiting and rewriting of the survival narrative raises the question of its malleability, its protean nature and its ability to transform and adapt to contemporary concerns. In most survival stories, crossing a sea or an ocean is rarely linear it is an odyssey that involves detours and bypasses that disorient and transform characters, stories and readers. Pi’s journey across the Pacific Ocean on a lifeboat with a full-grown Bengal tiger named Richard Parker lasts 227 days and gives rise to a narrative of trial, self-discovery and spiritual development. These are the premises upon which Martel wrote Life of Pi, the story of a young Indian boy named Pi (short for Piscine Patel) who leaves his native country in the late 1970s with his family and the remaining animals of their zoo to move to Canada in the hope of a better life away from the Indian state of emergency.

After the sinking of the ship that was supposed to take them to Canada, the hyena eats the zebra, kills the orang-utan before being killed and eaten by the tiger whose only companion in the lifeboat is a teenage boy.

1In her review of Yann Martel’s novel Life of Pi in the Sunday Times, Margaret Atwood wrote that the novel told a “far-fetched story you can’t quite swallow whole” ( Intent 224) about a sixteen-year-old Indian boy, a spotted hyena, a zebra, an orang-utan and a 450-pound Bengal tiger in a lifeboat in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)